Overview

RESTful is not a new term. It refers to an architectural style where web services receive and send data from and to client apps. The goal of these applications is to centralize data that different client apps will use.

Choosing the right tools to write RESTful services is crucial since we need to care about scalability, maintenance, documentation, and all other relevant aspects. The ASP.NET Core gives us a powerful, easy to use API that is great to achieve these goals.

In this article, I’ll show you how to write a well structured RESTful API for an “almost” real world scenario, using the ASP.NET Core framework. I’m going to detail common patterns and strategies to simplify the development process.

I’ll also show you how to integrate common frameworks and libraries, such as Entity Framework Core and AutoMapper, to deliver the necessary functionalities.

Prerequisites

I expect you to have knowledge of object-oriented programming concepts.

Even though I’m going to cover many details of the C# programming language, I recommend you to have basic knowledge of this subject.

I also assume you know what REST is, how the HTTP protocol works, what are API endpoints and what is JSON. The final requirement is that you understand how relational databases work.

To code along with me, you will have to install the .NET Core 2.2, as well as Postman, the tool I’m going to use to test the API. I recommend you to use a code editor such as Visual Studio Code to develop the API. Choose the code editor you prefer. If you choose this code editor, I recommend you to install the C# extension to have better code highlighting.

You can find a link to the Github repository of the API at the end of this article, to check the final result.

The Scope

Let’s write a fictional web API for a supermarket. Let’s imagine we have to implement the following scope:

- Create a RESTful service that allows client applications to manage the supermarket’s product catalog. It needs to expose endpoints to create, read, edit and delete products categories, such as dairy products and cosmetics, and also to manage products of these categories.

- For categories, we need to store their names. For products, we need to store their names, unit of measurement (for example, KG for products measured by weight), quantity in the package (for example, 10 if the product is a pack of biscuits) and their respective categories.

To simplify the example, I won’t handle products in stock, product shipping, security and any other functionality. The given scope is enough to show you how ASP.NET Core works.

To develop this service, we basically need two API endpoints: one to manage categories and one to manage products. In terms of JSON communication, we can think of responses as follow:

API endpoint: /api/categories

JSON Response (for GET requests):

{

[

{ "id": 1, "name": "Fruits and Vegetables" },

{ "id": 2, "name": "Breads" },

… // Other categories

]

}

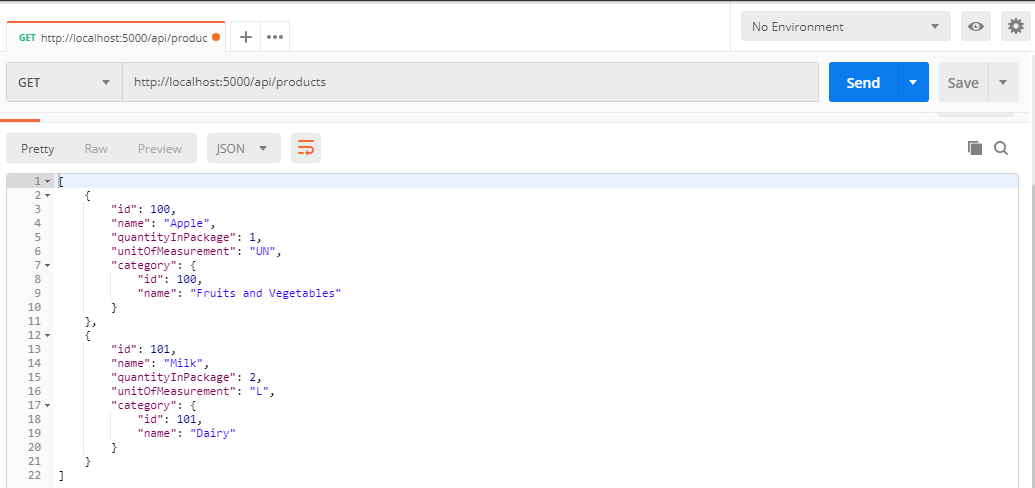

API endpoint: /api/products

JSON Response (for GET requests):

{

[

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Sugar",

"quantityInPackage": 1,

"unitOfMeasurement": "KG"

"category": {

"id": 3,

"name": "Sugar"

}

},

… // Other products

]

}

Let’s get started writing the application.

Step 1 — Creating the API

First of all, we have to create the folders structure for the web service, and then we have to use the .NET CLI tools to scaffold a basic web API. Open the terminal or command prompt (it depends on the operating system you are using) and type the following commands, in sequence:

mkdir src/Supermarket.API

cd src/Supermarket.API

dotnet new webapi

The first two commands simply create a new directory for the API and change the current location to the new folder. The last one generates a new project following the Web API template, that is the kind of application we’re developing.

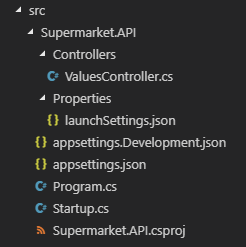

The new directory now will have the following structure:

Structure Overview

An ASP.NET Core application consists of a group of middlewares (small pieces of the application attached to the application pipeline, that handle requests and responses) configured in the Startup class. If you’ve already worked with frameworks like Express.js before, this concept isn’t new to you.

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to add services to the container.

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc().SetCompatibilityVersion(CompatibilityVersion.Version_2_2);

}

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the HTTP request pipeline.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IHostingEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

else

{

// The default HSTS value is 30 days. You may want to change this for production scenarios, see https://aka.ms/aspnetcore-hsts.

app.UseHsts();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseMvc();

}

}

When the application starts, the Main method, from the Program class, is called. It creates a default web host using the startup configuration, exposing the application via HTTP through a specific port (by default, port 5000 for HTTP and 5001 for HTTPS).

namespace Supermarket.API

{

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

CreateWebHostBuilder(args).Build().Run();

}

public static IWebHostBuilder CreateWebHostBuilder(string[] args) =>

WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.UseStartup<Startup>();

}

}

Take a look at the ValuesController class inside the Controllers folder. It exposes methods that will be called when the API receives requests through the route /api/values.

[Route("api/[controller]")]

[ApiController]

public class ValuesController : ControllerBase

{

// GET api/values

[HttpGet]

public ActionResult<IEnumerable<string>> Get()

{

return new string[] { "value1", "value2" };

}

// GET api/values/5

[HttpGet("{id}")]

public ActionResult<string> Get(int id)

{

return "value";

}

// POST api/values

[HttpPost]

public void Post([FromBody] string value)

{

}

// PUT api/values/5

[HttpPut("{id}")]

public void Put(int id, [FromBody] string value)

{

}

// DELETE api/values/5

[HttpDelete("{id}")]

public void Delete(int id)

{

}

}

Don’t worry if you don’t understand some part of this code. I’m going to detail each one when developing the necessary API endpoints. For now, simply delete this class, since we’re not going to use it.

Step 2 — Creating the Domain Models

I’m going to apply some design concepts that will keep the application simple and easy to maintain.

Writing code that can be understood and maintained by yourself is not this difficult, but you have to keep in mind that you’ll work as part of a team. If you don’t take care on how you write your code, the result will be a monster that will give you and your teammates constant headaches. It sounds extreme, right? But believe me, that’s the truth.

Let’s start by writing the domain layer. This layer will have our models classes, the classes that will represent our products and categories, as well as repositories and services interfaces. I’ll explain these last two concepts in a while.

Inside the Supermarket.API directory, create a new folder called Domain. Within the new domain folder, create another one called Models. The first model we have to add to this folder is the Category. Initially, it will be a simple Plain Old CLR Object (POCO) class. It means the class will have only properties to describe its basic information.

using System.Collections.Generic;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Models

{

public class Category

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public IList<Product> Products { get; set; } = new List<Product>();

}

}

The class has an Id property, to identify the category, and a Nameproperty. We also have a Products property. This last one will be used by Entity Framework Core, the ORM most ASP.NET Core applications use to persist data into a database, to map the relationship between categories and products. It also makes sense thinking in terms of object-oriented programming, since a category has many related products.

We also have to create the product model. At the same folder, add a new Product class.

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Models

{

public class Product

{

public int Id {get; set; }

public string Name {get; set; }

public short QuantityInPackage {get; set; }

public EUnitOfMeasurement UnitOfMeasurement {get; set; }

public int CategoryId {get; set; }

public Category Category {get; set; }

}

}

The product also has properties for the Id and name. The is also a property QuantityInPackage, that tells how many units of the product we have in one pack (remember the biscuits example of the application scope) and a UnitOfMeasurement property. This one is represented by an enum type, that represents an enumeration of possible units of measurement. The last two properties, CategoryId and Category will be used by the ORM to map the relationship between products and categories. It indicates that a product has one, and only one, category.

Let’s define the last part of our domain models, the EUnitOfMeasurementenum.

By convention, enums doesn’t need to start with an “E” in front of their names, but in some libraries and frameworks you’ll find this prefix as a way to distinguish enums from interfaces and classes.

using System.ComponentModel;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Models

{

public enum EUnitOfMeasurement : byte

{

[Description("UN")]

Unity = 1,

[Description("MG")]

Milligram = 2,

[Description("G")]

Gram = 3,

[Description("KG")]

Kilogram = 4,

[Description("L")]

Liter = 5

}

}

The code is really straightforward. Here we defined only a handful of possibilities for units of measurement, however, in a real supermarket system, you may have many other units of measurement, and maybe a separate model for that.

Notice the Description attribute applied over every enumeration possibility. An attribute is a way to define metadata over classes, interfaces, properties and other components of the C# language. In this case, we’ll use it to simplify the responses of the products API endpoint, but you don’t have to care about it for now. We’ll come back here later.

Our basic models are ready to be used. Now we can start writing the API endpoint that is going to manage all categories.

Step 3 — The Categories API

In the Controllers folder, add a new class called CategoriesController.

By convention, all classes in this folder that end with the suffix “Controller”will become controllers of our application. It means they are going to handle requests and responses. You have to inherit this class from the Controllerclass, defined in the namespace Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.

A namespace consists of a group of related classes, interfaces, enums, and structs. You can think of it as something similar to modules of the Javascript language, or packages from Java.

The new controller should respond through the route /api/categories. We achieve this by adding the Route attribute above the class name, specifying a placeholder that indicates that the route should use the class name without the controller suffix, by convention.

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

namespace Supermarket.API.Controllers

{

[Route("/api/[controller]")]

public class CategoriesController : Controller

{

}

}

Let’s start handling GET requests. First of all, when someone requests data from /api/categories via GET verb, the API needs to return all categories. We can create a category service for this purpose.

Conceptually, a service is basically a class or interface that defines methods to handle some business logic. It is a common practice in many different programming languages to create services to handle business logic, such as authentication and authorization, payments, complex data flows, caching and tasks that require some interaction between other services or models.

Using services, we can isolate the request and response handling from the real logic needed to complete tasks.

The service we’re going to create initially will define a single behavior, or method: a listing method. We expect that this method returns all existing categories in the database.

For simplicity, we won’t deal with data pagination or filtering in this case. I’ll write an article in the future showing how to easily handle these features.

To define an expected behavior for something in C# (and in other object-oriented languages, such as Java, for example), we define an interface. An interface tells how something should work, but does not implement the real logic for the behavior. The logic is implemented in classes that implement the interface. If this concept isn’t clear for you, don’t worry. You’ll understand it in a while.

Within the Domain folder, create a new directory called Services. There, add an interface called ICategoryService. By convention, all interfaces should start with the capital letter “I” in C#. Define the interface code as follows:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Services

{

public interface ICategoryService

{

Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync();

}

}

The implementations of the ListAsync method must asynchronously return an enumeration of categories.

The Task class, encapsulating the return, indicates asynchrony. We need to think in an asynchronous method due to the fact that we have to wait for the database to complete some operation to return the data, and this process can take a while. Notice also the “async” suffix. It’s a convention that indicates that our method should be executed asynchronously.

We have a lot of conventions, right? I personally like it, because it keeps applications easy to read, even if you’re new to a company that uses .NET technology.

If you come from a language such as Javascript or another non-strongly typed language, this concept may seem strange.

Interfaces allow us to abstract the desired behavior from the real implementation. Using a mechanism known as dependency injection, we can implement these interfaces and isolate them from other components.

Basically, when you use dependency injection, you define some behaviors using an interface. Then, you create a class that implements the interface. Finally, you bind the references from the interface to the class you created.

“ – It sounds really confusing. Can’t we simply create a class that does these things for us?”

Let’s continue implementing our API and you will understand why to use this approach.

Change the CategoriesController code as follows:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Services;

namespace Supermarket.API.Controllers

{

[Route("/api/[controller]")]

public class CategoriesController : Controller

{

private readonly ICategoryService _categoryService;

public CategoriesController(ICategoryService categoryService)

{

_categoryService = categoryService;

}

[HttpGet]

public async Task<IEnumerable<Category>> GetAllAsync()

{

var categories = await _categoryService.ListAsync();

return categories;

}

}

}

I have defined a constructor function for our controller (a constructor is called when a new instance of a class is created), and it receives an instance of ICategoryService. It means the instance can be anything that implements the service interface. I store this instance in a private, read-only field _categoryService. We’ll use this field to access the methods of our category service implementation.

By the way, the underscore prefix is another common convention to denote a field. This convention, in special, is not recommended by the official naming convention guideline of .NET, but it is a very common practice as a way to avoid having to use the “this” keyword to distinguish class fields from local variables. I personally think it’s much cleaner to read, and a lot of frameworks and libraries use this convention.

Below the constructor, I defined the method that is going to handle requests for /api/categories. The HttpGet attribute tells the ASP.NET Core pipeline to use it to handle GET requests (this attribute can be omitted, but it’s better to write it for easier legibility).

The method uses our category service instance to list all categories and then returns the categories to the client. The framework pipeline handles the serialization of data to a JSON object. The IEnumerable<Category>type tells the framework that we want to return an enumeration of categories, and the Task type, preceded by the async keyword, tells the pipeline that this method should be executed asynchronously. Finally, when we define an async method, we have to use the await keyword for tasks that can take a while.

Ok, we defined the initial structure of our API. Now, it is necessary to really implement the categories service.

Step 4 — Implementing the Categories Service

In the root folder of the API (the Supermarket.API folder), create a new one called Services. Here we’ll put all services implementations. Inside the new folder, add a new class called CategoryService. Change the code as follows:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Services;

namespace Supermarket.API.Services

{

public class CategoryService : ICategoryService

{

public async Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync()

{

}

}

}

It’s simply the basic code for the interface implementation, but we still don’t handle any logic. Let’s think in how the listing method should work.

We need to access the database and return all categories, then we need to return this data to the client.

A service class is not a class that should handle data access. There is a pattern called Repository Pattern that is used to manage data from databases.

When using the Repository Pattern, we define repository classes, that basically encapsulate all logic to handle data access. These repositories expose methods to list, create, edit and delete objects of a given model, the same way you can manipulate collections. Internally, these methods talk to the database to perform CRUD operations, isolating the database access from the rest of the application.

Our service needs to talk to a category repository, to get the list of objects.

Conceptually, a service can “talk” to one or more repositories or other services to perform operations.

It may seem redundant to create a new definition for handling the data access logic, but you will see in a while that isolating this logic from the service class is really advantageous.

Let’s create a repository that will be responsible for intermediating the database communication as a way to persist categories.

Step 5 — The Categories Repository and the Persistence Layer

Inside the Domain folder, create a new directory called Repositories. Then, add a new interface called ICategoryRespository.

The initial code is basically identical to the code of the service interface.

Having defined the interface, we can come back to the service class and finish implementing the listing method, using an instance of ICategoryRepositoryto return the data.

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Repositories;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Services;

namespace Supermarket.API.Services

{

public class CategoryService : ICategoryService

{

private readonly ICategoryRepository _categoryRepository;

public CategoryService(ICategoryRepository categoryRepository)

{

this._categoryRepository = categoryRepository;

}

public async Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync()

{

return await _categoryRepository.ListAsync();

}

}

}

Now we have to implement the real logic of the category repository. Before doing it, we have to think about how we are going to access the database.

By the way, we still don’t have a database!

We’ll use the Entity Framework Core (I’ll call it EF Core for simplicity) as our database ORM. This framework comes with ASP.NET Core as its default ORM and exposes a friendly API that allows us to map classes of our applications to database tables.

The EF Core also allows us to design our application first, and then generate a database according to what we defined in our code. This technique is called code first. We’ll use the code first approach to generate a database (in this example, in fact, I’m going to use an in-memory database, but you will be able to easily change it to a SQL Server or MySQL server instance, for example).

In the root folder of the API, create a new directory called Persistence. This directory is going to have everything we need to access the database, such as repositories implementations.

Inside the new folder, create a new directory called Contexts, and then add a new class called AppDbContext. This class must inherit DbContext, a class EF Core uses to map your models to database tables. Change the code in the following way:

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Persistence.Contexts

{

public class AppDbContext : DbContext

{

public AppDbContext(DbContextOptions<AppDbContext> options) : base(options)

{

}

}

}

The constructor we added to this class is responsible for passing the database configuration to the base class through dependency injection. You’ll see in a moment how this works.

Now, we have to create two DbSet properties. These properties are sets(collections of unique objects) that map models to database tables.

Also, we have to map the models’ properties to the respective table columns, specifying which properties are primary keys, which are foreign keys, the column types, etc. We can do this overriding the method OnModelCreating, using a feature called Fluent API to specify the database mapping. Change the AppDbContext class as follows:

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

namespace Supermarket.API.Persistence.Contexts

{

public class AppDbContext : DbContext

{

public DbSet<Category> Categories { get; set; }

public DbSet<Product> Products { get; set; }

public AppDbContext(DbContextOptions<AppDbContext> options) : base(options) { }

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder builder)

{

base.OnModelCreating(builder);

builder.Entity<Category>().ToTable("Categories");

builder.Entity<Category>().HasKey(p => p.Id);

builder.Entity<Category>().Property(p => p.Id).IsRequired().ValueGeneratedOnAdd();

builder.Entity<Category>().Property(p => p.Name).IsRequired().HasMaxLength(30);

builder.Entity<Category>().HasMany(p => p.Products).WithOne(p => p.Category).HasForeignKey(p => p.CategoryId);

builder.Entity<Category>().HasData

(

new Category { Id = 100, Name = "Fruits and Vegetables" }, // Id set manually due to in-memory provider

new Category { Id = 101, Name = "Dairy" }

);

builder.Entity<Product>().ToTable("Products");

builder.Entity<Product>().HasKey(p => p.Id);

builder.Entity<Product>().Property(p => p.Id).IsRequired().ValueGeneratedOnAdd();

builder.Entity<Product>().Property(p => p.Name).IsRequired().HasMaxLength(50);

builder.Entity<Product>().Property(p => p.QuantityInPackage).IsRequired();

builder.Entity<Product>().Property(p => p.UnitOfMeasurement).IsRequired();

}

}

}

The code is intuitive.

We specify to which tables our models should be mapped. Also, we set the primary keys, using the method HasKey, the table columns, using the Property method, and some constraints such as IsRequired, HasMaxLength,and ValueGeneratedOnAdd, everything with lambda expressions in a “fluent way” (chaining methods).

Take a look at the following piece of code:

builder.Entity<Category>()

.HasMany(p => p.Products)

.WithOne(p => p.Category)

.HasForeignKey(p => p.CategoryId);

Here we’re specifying a relationship between tables. We say that a category has many products, and we set the properties that will map this relationship (Products, from Category class, and Category, from Product class). We also set the foreign key (CategoryId).

There is also a configuration for seeding data, through the method HasData:

builder.Entity<Category>().HasData

(

new Category { Id = 100, Name = "Fruits and Vegetables" },

new Category { Id = 101, Name = "Dairy" }

);

Here we simply add two example categories by default. That’s necessary to test our API endpoint after we finish it.

Notice: we’re manually setting the

Idproperties here because the in-memory provider requires it to work. I’m setting the identifiers to big numbers to avoid collision between auto-generated identifiers and seed data.

This limitation does not exist in true relational database providers, so if you want to use a database such as SQL Server, for example, you don’t have to specify these identifiers.

Having implemented the database context class, we can implement the categories repository. Add a new folder called Repositories inside the Persistence folder, and then add a new class called BaseRepository.

using Supermarket.API.Persistence.Contexts;

namespace Supermarket.API.Persistence.Repositories

{

public abstract class BaseRepository

{

protected readonly AppDbContext _context;

public BaseRepository(AppDbContext context)

{

_context = context;

}

}

}

This class is just an abstract class that all our repositories will inherit. An abstract class is a class that don’t have direct instances. You have to create direct classes to create the instances.

The BaseRepository receives an instance of our AppDbContext through dependency injection and exposes a protected property (a property that can only be accessible by the children classes) called _context, that gives access to all methods we need to handle database operations.

Add a new class on the same folder called CategoryRepository. Now we’ll really implement the repository logic:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Repositories;

using Supermarket.API.Persistence.Contexts;

namespace Supermarket.API.Persistence.Repositories

{

public class CategoryRepository : BaseRepository, ICategoryRepository

{

public CategoryRepository(AppDbContext context) : base(context)

{

}

public async Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync()

{

return await _context.Categories.ToListAsync();

}

}

}

The repository inherits the BaseRepository and implements ICategoryRepository.

Notice how simple it is to implement the listing method. We use the Categories database set to access the categories table and then call the extension method ToListAsync, which is responsible for transforming the result of a query into a collection of categories.

The EF Core translates our method call to a SQL query, the most efficient way as possible. The query is only executed when you call a method that will transform your data into a collection, or when you use a method to take specific data.

We now have a clean implementation of the categories controller, the service and repository.

We have separated concerns, creating classes that only do what they are supposed to do.

The last step before testing the application is to bind our interfaces to the respective classes using the ASP.NET Core dependency injection mechanism.

Step 6 — Configuring Dependency Injection

It’s time for you to finally understand how this concept works.

In the root folder of the application, open the Startup class. This class is responsible for configuring all kinds of configurations when the application starts.

The ConfigureServices and Configure methods are called at runtime by the framework pipeline to configure how the application should work and which components it must use.

Have a look at the ConfigureServices method. Here we only have one line, that configures the application to use the MVC pipeline, which basically means the application is going to handle requests and responses using controller classes (there are more things happening here behind the scenes, but that’s what you need to know for now).

We can use the ConfigureServices method, accessing the servicesparameter, to configure our dependency bindings. Clean up the class code removing all comments and change the code as follows:

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Builder;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Hosting;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Repositories;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Services;

using Supermarket.API.Persistence.Contexts;

using Supermarket.API.Persistence.Repositories;

using Supermarket.API.Services;

namespace Supermarket.API

{

public class Startup

{

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc().SetCompatibilityVersion(CompatibilityVersion.Version_2_2);

services.AddDbContext<AppDbContext>(options => {

options.UseInMemoryDatabase("supermarket-api-in-memory");

});

services.AddScoped<ICategoryRepository, CategoryRepository>();

services.AddScoped<ICategoryService, CategoryService>();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IHostingEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

else

{

// The default HSTS value is 30 days. You may want to change this for production scenarios, see https://aka.ms/aspnetcore-hsts.

app.UseHsts();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseMvc();

}

}

}

Look at this piece of code:

services.AddDbContext<AppDbContext>(options => {

options.UseInMemoryDatabase("supermarket-api-in-memory");

});

Here we configure the database context. We tell ASP.NET Core to use our AppDbContext with an in-memory database implementation, that is identified by the string passed as an argument to our method. Usually, the in-memory provider is used when we write integration tests, but I’m using it here for simplicity. This way we don’t need to connect to a real database to test the application.

The configuration of these lines internally configures our database context for dependency injection using a scoped lifetime.

The scoped lifetime tells the ASP.NET Core pipeline that every time it needs to resolve a class that receives an instance of AppDbContext as a constructor argument, it should use the same instance of the class. If there is no instance in memory, the pipeline will create a new instance, and reuse it throughout all classes that need it, during a given request. This way, you don’t need to manually create the class instance when you need to use it.

There are other lifetime scopes that you can check reading the official documentation.

The dependency injection technique gives us many advantages, such as:

- Code reusability;

- Better productivity, since when we have to change implementation, we don’t need to bother to change a hundred places where you use that feature;

- You can easily test the application since we can isolate what we have to test using mocks (fake implementation of classes) where we have to pass interfaces as constructor arguments;

- When a class needs to receive more dependencies via a constructor, you don’t have to manually change all places where the instances are being created (that’s awesome!).

After configuring the database context, we also bind our service and repository to the respective classes.

services.AddScoped<ICategoryRepository, CategoryRepository>();

services.AddScoped<ICategoryService, CategoryService>();

Here we also use a scoped lifetime because these classes internally have to use the database context class. It makes sense to specify the same scope in this case.

Now that we configure our dependency bindings, we have to make a small change at the Program class, in order for the database to correctly seed our initial data. This step is only needed when using the in-memory database provider.

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.IO;

using System.Linq;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Hosting;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using Supermarket.API.Persistence.Contexts;

namespace Supermarket.API

{

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var host = BuildWebHost(args);

using(var scope = host.Services.CreateScope())

using(var context = scope.ServiceProvider.GetService<AppDbContext>())

{

context.Database.EnsureCreated();

}

host.Run();

}

public static IWebHost BuildWebHost(string[] args) =>

WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.UseStartup<Startup>()

.Build();

}

}

It was necessary to change the Main method to guarantee that our database is going to be “created” when the application starts since we’re using an in-memory provider. Without this change, the categories that we want to seed won’t be created.

With all the basic features implemented, it’s time to test our API endpoint.

Step 7 — Testing the Categories API

Open the terminal or command prompt in the API root folder, and type the following command:

dotnet run

The command above starts the application. The console is going to show an output similar to this:

info: Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Infrastructure[10403]

Entity Framework Core 2.2.0-rtm-35687 initialized ‘AppDbContext’ using provider ‘Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.InMemory’ with options: StoreName=supermarket-api-in-memory

info: Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Update[30100]

Saved 2 entities to in-memory store.

info: Microsoft.AspNetCore.DataProtection.KeyManagement.XmlKeyManager[0]

User profile is available. Using ‘C:\Users\evgomes\AppData\Local\ASP.NET\DataProtection-Keys’ as key repository and Windows DPAPI to encrypt keys at rest.

Hosting environment: Development

Content root path: C:\Users\evgomes\Desktop\Tutorials\src\Supermarket.API

Now listening on: https://localhost:5001

Now listening on: http://localhost:5000

Application started. Press Ctrl+C to shut down.

You can see that EF Core was called to initialize the database. The last lines show in which ports the application is running.

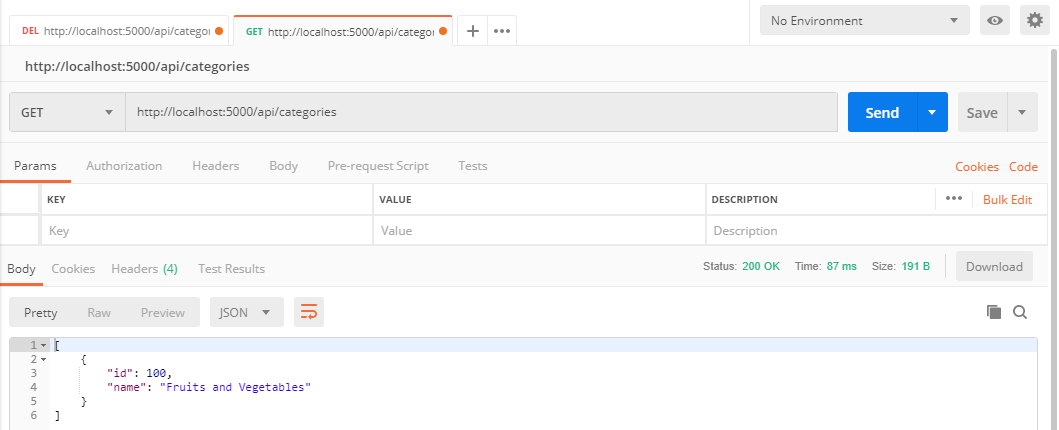

Open a browser and navigate to http://localhost:5000/api/categories (or to the URL displayed on the console output). If you see a security error because of HTTPS, just add an exception for the application.

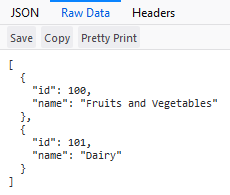

The browser is going to show the following JSON data as output:

[

{

"id": 100,

"name": "Fruits and Vegetables",

"products": []

},

{

"id": 101,

"name": "Dairy",

"products": []

}

]

Here we see the data we added to the database when we configured the database context. This output confirms that our code is working.

You created a GET API endpoint with really few lines of code, and you have a code structure that is really easy to change due to the architecture of the API.

Now, it’s time to show you how easy is to change this code when you have to adjust it due to business needs.

Step 8 — Creating a Category Resource

If you remember the specification of the API endpoint, you have noticed that our actual JSON response has one extra property: an array of products. Take a look at the example of the desired response:

{

[

{ "id": 1, "name": "Fruits and Vegetables" },

{ "id": 2, "name": "Breads" },

… // Other categories

]

}

The products array is present at our current JSON response because our Category model has a Products property, needed by EF Core to correct map the products of a given category.

We don’t want this property in our response, but we can’t change our model class to exclude this property. It would cause EF Core to throw errors when we try to manage categories data, and it would also break our domain model design because it does not make sense to have a product category that doesn’t have products.

To return JSON data containing only the identifiers and names of the supermarket categories, we have to create a resource class.

A resource class is a class that contains only basic information that will be exchanged between client applications and API endpoints, generally in form of JSON data, to represent some particular information.

All responses from API endpoints must return a resource.

It is a bad practice to return the real model representation as the response since it can contain information that the client application does not need or that it doesn’t have permission to have (for example, a user model could return information of the user password, which would be a big security issue).

We need a resource to represent only our categories, without the products.

Now that you know what a resource is, let’s implement it. First of all, stop the running application pressing Ctrl + C at the command line. In the root folder of the application, create a new folder called Resources. There, add a new class called CategoryResource.

namespace Supermarket.API.Resources

{

public class CategoryResource

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

}

We have to map our collection of category models, that is provided by our category service, to a collection of category resources.

We’ll use a library called AutoMapper to handle mapping between objects. AutoMapper is a very popular library in the .NET world, and it is used in many commercial and open source projects.

Type the following lines into the command line to add AutoMapper to our application:

dotnet add package AutoMapper

dotnet add package AutoMapper.Extensions.Microsoft.DependencyInjection

To use AutoMapper, we have to do two things:

- Register it for dependency injection;

- Create a class that will tell AutoMapper how to handle classes mapping.

First of all, open the Startup class. In the ConfigureServices method, after the last line, add the following code:

services.AddAutoMapper();

This line handles all necessary configurations of AutoMapper, such as registering it for dependency injection and scanning the application during startup to configure mapping profiles.

Now, in the root directory, add a new folder called Mapping, then add a class called ModelToResourceProfile. Change the code this way:

using AutoMapper;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Resources;

namespace Supermarket.API.Mapping

{

public class ModelToResourceProfile : Profile

{

public ModelToResourceProfile()

{

CreateMap<Category, CategoryResource>();

}

}

}

The class inherits Profile, a class type that AutoMapper uses to check how our mappings will work. On the constructor, we create a map between the Category model class and the CategoryResource class. Since the classes’ properties have the same names and types, we don’t have to use any special configuration for them.

The final step consists of changing the categories controller to use AutoMapper to handle our objects mapping.

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using AutoMapper;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Services;

using Supermarket.API.Resources;

namespace Supermarket.API.Controllers

{

[Route("/api/[controller]")]

public class CategoriesController : Controller

{

private readonly ICategoryService _categoryService;

private readonly IMapper _mapper;

public CategoriesController(ICategoryService categoryService, IMapper mapper)

{

_categoryService = categoryService;

_mapper = mapper;

}

[HttpGet]

public async Task<IEnumerable<CategoryResource>> GetAllAsync()

{

var categories = await _categoryService.ListAsync();

var resources = _mapper.Map<IEnumerable<Category>, IEnumerable<CategoryResource>>(categories);

return resources;

}

}

}

I changed the constructor to receive an instance of IMapper implementation. You can use these interface methods to use AutoMapper mapping methods.

I also changed the GetAllAsync method to map our enumeration of categories to an enumeration of resources using the Map method. This method receives an instance of the class or collection we want to map and, through generic type definitions, it defines to what type of class or collection must be mapped.

Notice that we easily changed the implementation without having to adapt the service class or repository, simply by injecting a new dependency (IMapper) to the constructor.

Dependency injection makes your application maintainable and easy to change since you don’t have to break all your code implementation to add or remove features.

You probably realized that not only the controller class but all classes that receive dependencies (including the dependencies themselves) were automatically resolved to receive the correct classes according to the binding configurations.

Dependency injection is amazing, isn’t it?

Now, start the API again using dotnet run command and head over to http://localhost:5000/api/categories to see the new JSON response.

We already have our GET endpoint. Now, let’s create a new endpoint to POST (create) categories.

Step 9 — Creating new Categories

When dealing with resources creation, we have to care about many things, such as:

- Data validation and data integrity;

- Authorization to create resources;

- Error handling;

- Logging.

Also, there is a very popular framework called ASP.NET Identity that provides built-in solutions regarding security and users registration that you can use in your applications. It includes providers to work with EF Core, such as a built-in IdentityDbContext you can use.

Let’s write an HTTP POST endpoint that’s going to cover the other scenarios (except for logging, that can change according to different scopes and tools).

Before creating the new endpoint, we need a new resource. This resource will map data that client applications send to this endpoint (in this case, the category name) to a class of our application.

Since we’re creating a new category, we don’t have an ID yet, and it means we need a resource that represents a category containing only its name.

In the Resources folder, add a new class called SaveCategoryResource:

using System.ComponentModel.DataAnnotations;

namespace Supermarket.API.Resources

{

public class SaveCategoryResource

{

[Required]

[MaxLength(30)]

public string Name { get; set; }

}

}

Notice the Required and MaxLength attributes applied over the Nameproperty. These attributes are called data annotations. The ASP.NET Core pipeline uses this metadata to validate requests and responses. As the names suggest, the category name is required and has a max length of 30 characters.

Now let’s define the shape of the new API endpoint. Add the following code to the categories controller:

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> PostAsync([FromBody] SaveCategoryResource resource)

{

}

We tell the framework that this is an HTTP POST endpoint using the HttpPost attribute.

Notice the response type of this method, Task<IActionResult>. Methods present in controller classes are called actions, and they have this signature because we can return more than one possible result after the application executes the action.

In this case, if the category name is invalid, or if something goes wrong, we have to return a 400 code (bad request) response, containing generally an error message that client apps can use to treat the problem, or we can have a 200 response (success) with data if everything goes ok.

There are many types of action types you can use as response, but generally, we can use this interface, and ASP.NET Core will use a default class for that.

The FromBody attribute tells ASP.NET Core to parse the request body data into our new resource class. It means that when a JSON containing the category name is sent to our application, the framework will automatically parse it to our new class.

Now, let’s implement our route logic. We have to follow some steps to successfully create a new category:

- First, we have to validate the incoming request. If the request is invalid, we have to return a bad request response containing the error messages;

- Then, if the request is valid, we have to map our new resource to our category model class using AutoMapper;

- We now need to call our service, telling it to save our new category. If the saving logic is executed without problems, it should return a response containing our new category data. If not, it should give us an indication that the process failed, and a potential error message;

- Finally, if there is an error, we return a bad request. If not, we map our new category model to a category resource and return a success response to the client, containing the new category data.

It seems to be complicated, but it is really easy to implement this logic using the service architecture we structured for our API.

Let’s get started by validating the incoming request.

Step 10 — Validating the Request Body Using the Model State

ASP.NET Core controllers have a property called ModelState. This property is filled during request execution before reaching our action execution. It’s an instance of ModelStateDictionary, a class that contains information such as whether the request is valid and potential validation error messages.

Change the endpoint code as follows:

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> PostAsync([FromBody] SaveCategoryResource resource)

{

if (!ModelState.IsValid)

return BadRequest(ModelState.GetErrorMessages());

}

The code checks if the model state (in this case, the data sent in the request body) is invalid, checking our data annotations. If it isn’t, the API returns a bad request (with 400 status code) and the default error messages our annotations metadata provided.

The ModelState.GetErrorMessages()method isn’t implemented yet. It’s an extension method (a method that extends the functionality of an already existing class or interface) that I’m going to implement to convert the validation errors into simple strings to return to the client.

Add a new folder Extensions in the root of our API and then add a new class ModelStateExtensions.

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.ModelBinding;

namespace Supermarket.API.Extensions

{

public static class ModelStateExtensions

{

public static List<string> GetErrorMessages(this ModelStateDictionary dictionary)

{

return dictionary.SelectMany(m => m.Value.Errors)

.Select(m => m.ErrorMessage)

.ToList();

}

}

}

All extension methods should be static, as well as the classes where they are declared. It means they don’t handle specific instance data and that they’re loaded only once when the application starts.

The this keyword in front of the parameter declaration tells the C# compiler to treat it as an extension method. The result is that we can call it like a normal method of this class since we include the respective usingdirective where we want to use the extension.

The extension uses LINQ queries, a very useful feature of .NET that allows us to query and transform data using chainable expressions. The expressions here transform the validation error methods into a list of strings containing the error messages.

Import the namespace Supermarket.API.Extensions into the categories controller before going to the next step.

using Supermarket.API.Extensions;Let’s continue implementing our endpoint logic by mapping our new resource to a category model class.

Step 11 — Mapping the new Resource

We have already defined a mapping profile to transform models into resources. Now we need a new profile that does the inverse.

Add a new class ResourceToModelProfile into the Mapping folder:

using AutoMapper;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Resources;

namespace Supermarket.API.Mapping

{

public class ResourceToModelProfile : Profile

{

public ResourceToModelProfile()

{

CreateMap<SaveCategoryResource, Category>();

}

}

}

Nothing new here. Thanks to the magic of dependency injection, AutoMapper will automatically register this profile when the application starts, and we don’t have to change any other place to use it.

Now we can map our new resource to the respective model class:

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> PostAsync([FromBody] SaveCategoryResource resource)

{

if (!ModelState.IsValid)

return BadRequest(ModelState.GetErrorMessages());

var category = _mapper.Map<SaveCategoryResource, Category>(resource);

}

Step 12 — Applying the Request-Response Pattern to Handle the Saving Logic

Now we have to implement the most interesting logic: to save a new category. We expect our service to do it.

The saving logic may fail due to problems when connecting to the database, or maybe because any internal business rule invalidates our data.

If something goes wrong, we can’t simply throw an error, because it could stop the API, and the client application wouldn’t know how to handle the problem. Also, we potentially would have some logging mechanism that would log the error.

The contract of the saving method, it means, the signature of the method and response type, needs to indicate us if the process was executed correctly. If the process goes ok, we’ll receive the category data. If not, we have to receive, at least, an error message telling why the process failed.

We can implement this feature by applying the request-response pattern. This enterprise design pattern encapsulates our request and response parameters into classes as a way to encapsulate information that our services will use to process some task and to return information to the class that is using the service.

This pattern gives us some advantages, such as:

- If we need to change our service to receive more parameters, we don’t have to break its signature;

- We can define a standard contract for our request and/or responses;

- We can handle business logic and potential fails without stopping the application process, and we won’t need to use tons of try-catch blocks.

Let’s create a standard response type for our services methods that handle data changes. For every request of this type, we want to know if the request is executed with no problems. If it fails, we want to return an error message to the client.

In the Domain folder, inside Services, add a new directory called Communication. Add a new class there called BaseResponse.

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Services.Communication

{

public abstract class BaseResponse

{

public bool Success { get; protected set; }

public string Message { get; protected set; }

public BaseResponse(bool success, string message)

{

Success = success;

Message = message;

}

}

}

That’s an abstract class that our response types will inherit.

The abstraction defines a Success property, which will tell whether requests were completed successfully, and a Message property, that will have the error message if something fails.

Notice that these properties are required and only inherited classes can set this data because children classes have to pass this information through the constructor function.

Tip: it’s not a good practice to define base classes for everything, because base classes couple your code and prevent you from easily modifying it. Prefer to use composition over inheritance.

For the scope of this API, it’s not really a problem to use base classes, since our services won’t grow much. If you realize that a service or application will grow and change frequently, avoid using a base class.

Now, in the same folder, add a new class called SaveCategoryResponse.

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Services.Communication

{

public class SaveCategoryResponse : BaseResponse

{

public Category Category { get; private set; }

private SaveCategoryResponse(bool success, string message, Category category) : base(success, message)

{

Category = category;

}

/// <summary>

/// Creates a success response.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="category">Saved category.</param>

/// <returns>Response.</returns>

public SaveCategoryResponse(Category category) : this(true, string.Empty, category)

{ }

/// <summary>

/// Creates am error response.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="message">Error message.</param>

/// <returns>Response.</returns>

public SaveCategoryResponse(string message) : this(false, message, null)

{ }

}

}

The response type also sets a Category property, which is going to contain our category data if the request successfully finishes.

Notice that I’ve defined three different constructors for this class:

- A private one, which is going to pass the success and message parameters to the base class, and also sets the

Categoryproperty; - A constructor that receives only the category as a parameter. This one will create a successful response, calling the private constructor to set the respective properties;

- A third constructor that only specifies the message. This one will be used to create a failure response.

Because C# supports multiple constructors, we simplified the response creation without defining different method to handle this, just by using different constructors.

Now we can change our service interface to add the new save method contract.

Change the ICategoryService interface as follows:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Models;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Services.Communication;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Services

{

public interface ICategoryService

{

Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync();

Task<SaveCategoryResponse> SaveAsync(Category category);

}

}

We’ll simply pass a category to this method and it will handle all logic necessary to save the model data, orchestrating repositories and other necessary services to do that.

Notice I’m not creating a specific request class here since we don’t need any other parameters to perform this task. There is a concept in computer programming called KISS — short for Keep it Simple, Stupid. Basically, it says that you should keep your application as simple as possible.

Remember this when designing your applications: apply only what you need to solve a problem. Don’t over-engineer your application.

Now we can finish our endpoint logic:

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> PostAsync([FromBody] SaveCategoryResource resource)

{

if (!ModelState.IsValid)

return BadRequest(ModelState.GetErrorMessages());

var category = _mapper.Map<SaveCategoryResource, Category>(resource);

var result = await _categoryService.SaveAsync(category);

if (!result.Success)

return BadRequest(result.Message);

var categoryResource = _mapper.Map<Category, CategoryResource>(result.Category);

return Ok(categoryResource);

}

After validating the request data and mapping the resource to our model, we pass it to our service to persist the data.

If something fails, the API returns a bad request. If not, the API maps the new category (now including data such as the new Id) to our previously created CategoryResource and sends it to the client.

Now let’s implement the real logic for the service.

Step 13 — The Database Logic and the Unit of Work Pattern

Since we’re going to persist data into the database, we need a new method in our repository.

Add a new AddAsync method to the ICategoryRepository interface:

public interface ICategoryRepository

{

Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync();

Task AddAsync(Category category);

}

Now, let’s implement this method at our real repository class:

public class CategoryRepository : BaseRepository, ICategoryRepository

{

public CategoryRepository(AppDbContext context) : base(context)

{ }

public async Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync()

{

return await _context.Categories.ToListAsync();

}

public async Task AddAsync(Category category)

{

await _context.Categories.AddAsync(category);

}

}

Here we’re simply adding a new category to our set.

When we add a class to a DBSet<>, EF Core starts tracking all changes that happen to our model and uses this data at the current state to generate queries that will insert, update or delete models.

The current implementation simply adds the model to our set, but our data still won’t be saved.

There is a method called SaveChanges present at the context class that we have to call to really execute the queries into the database. I didn’t call it here because a repository shouldn’t persist data, it’s just an in-memory collection of objects.

This subject is very controversial even between experienced .NET developers, but let me explain to you why you shouldn’t call SaveChanges in repository classes.

We can think of a repository conceptually as any other collection present at the .NET framework. When dealing with a collection in .NET (and many other programming languages, such as Javascript and Java), you generally can:

- Add new items to it (like when you push data to lists, arrays, and dictionaries);

- Find or filter items;

- Remove an item from the collection;

- Replace a given item, or update it.

Think of a list from the real world. Imagine you’re writing a shopping list to buy things at a supermarket (what a coincidence, no?).

In the list, you write all the fruits you need to buy. You can add fruits to this list, remove a fruit if you give up buying it, or you can replace a fruit’s name. But you can’t save fruits into the list. It doesn’t make sense to say such a thing in plain English.

Tip: when designing classes and interfaces in object-oriented programming languages, try to use natural language to check if what you’re doing seems to be correct.

It makes sense, for instance, to say that a man implements a person interface, but it doesn’t make sense to say that a man implements an account.

If you want to “save” the fruits lists (in this case, to buy all fruits), you pay it and the supermarket processes the stock data to check if they have to buy more fruits from a provider or not.

The same logic can be applied when programming. Repositories shouldn’t save, update or delete data. Instead, they should delegate it to a different class to handle this logic.

There is another problem when saving data directly into a repository: you can’t use transactions.

Imagine that our application has a logging mechanism that stores some username and the action performed every time a change is made to the API data.

Now imagine that, for some reason, you have a call to a service that updates the username (it’s not a common scenario, but let’s consider it).

You agree that to change the username in a fictional users table, you first have to update all logs to correctly tell who performed that operation, right?

Now imagine we have implemented the update method for users and logs in different repositories, and them both call SaveChanges. What happens if one of these methods fails in the middle of the updating process? You’ll end up with data inconsistency.

We should save our changes into the database only after everything finishes. To do this, we have to use a transaction, that is basically a feature most databases implement to save data only after a complex operation finishes.

“ – Ok, so if we can’t save things here, where should we do it?”

A common pattern to handle this issue is the Unit of Work Pattern. This pattern consists of a class that receives our AppDbContext instance as a dependency and exposes methods to start, complete or abort transactions.

We’ll use a simple implementation of a unit of work to approach our problem here.

Add a new interface inside the Repositories folder of the Domain layer called IUnitOfWork:

using System.Threading.Tasks;

namespace Supermarket.API.Domain.Repositories

{

public interface IUnitOfWork

{

Task CompleteAsync();

}

}

As you can see, it only exposes a method that will asynchronously complete data management operations.

Let’s add the real implementation now.

Add a new class called UnitOfWork at the RepositoriesRepositories folder of the Persistence layer:

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Supermarket.API.Domain.Repositories;

using Supermarket.API.Persistence.Contexts;

namespace Supermarket.API.Persistence.Repositories

{

public class UnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork

{

private readonly AppDbContext _context;

public UnitOfWork(AppDbContext context)

{

_context = context;

}

public async Task CompleteAsync()

{

await _context.SaveChangesAsync();

}

}

}

That’s a simple, clean implementation that will only save all changes into the database after you finish modifying it using your repositories.

If you research implementations of the Unit of Work pattern, you’ll find more complex ones implementing rollback operations.

Since EF Core already implement the repository pattern and unit of work behind the scenes, we don’t have to care about a rollback method.

Separating the persistence logic from business rules gives many advantages in terms of code reusability and maintenance. If we use EF Core directly, we’ll end up having more complex classes that won’t be so easy to change.

Imagine that in the future you decide to change the ORM framework to a different one, such as Dapper, for example, or if you have to implement plain SQL queries because of performance. If you couple your queries logic to your services, it will be difficult to change the logic, because you’ll have to do it in many classes.

Using the repository pattern, you can simply implement a new repository class and bind it using dependency injection.

As I said, EF Core implements the Unit of Work and Repository patterns behind the scenes. We can consider our DbSet<>properties as repositories. Also, SaveChanges only persists data in case of success for all database operations.

Now that you know what is a unit of work and why to use it with repositories, let’s implement the real service’s logic.

public class CategoryService : ICategoryService

{

private readonly ICategoryRepository _categoryRepository;

private readonly IUnitOfWork _unitOfWork;

public CategoryService(ICategoryRepository categoryRepository, IUnitOfWork unitOfWork)

{

_categoryRepository = categoryRepository;

_unitOfWork = unitOfWork;

}

public async Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync()

{

return await _categoryRepository.ListAsync();

}

public async Task<SaveCategoryResponse> SaveAsync(Category category)

{

try

{

await _categoryRepository.AddAsync(category);

await _unitOfWork.CompleteAsync();

return new SaveCategoryResponse(category);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

// Do some logging stuff

return new SaveCategoryResponse($"An error occurred when saving the category: {ex.Message}");

}

}

}

Thanks to our decoupled architecture, we can simply pass an instance of UnitOfWork as a dependency for this class.

Our business logic is pretty simple.

First, we try to add the new category to the database and then the API try to save it, wrapping everything inside a try-catch block.

If something fails, the API calls some fictional logging service and return a response indicating failure.

If the process finishes with no problems, the application returns a success response, sending our category data. Simple, right?

Tip: In real world applications, you shouldn’t wrap everything inside a generic try-catch block, but instead you should handle all possible errors separately.

Simply adding a try-catch block won’t cover most of the possible failing scenarios. Be sure to correct implement error handling.

The last step before testing our API is to bind the unit of work interface to its respective class.

Add this new line to the ConfigureServices method of the Startup class:

services.AddScoped<IUnitOfWork, UnitOfWork>();

Now let’s test it!

Step 14 — Testing our POST Endpoint using Postman

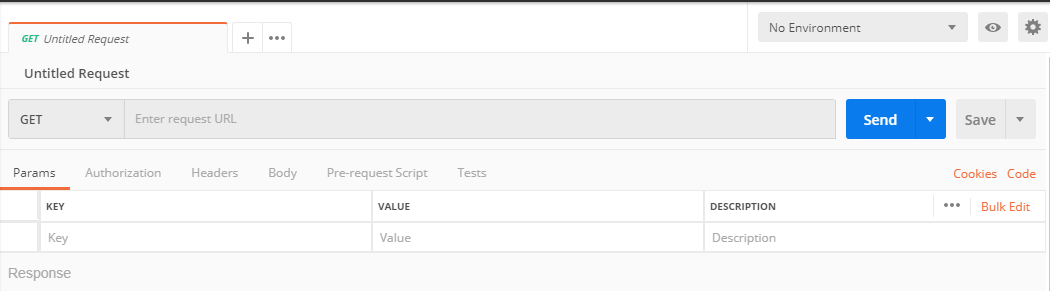

Start our application again using dotnet run.

We can’t use the browser to test a POST endpoint. Let’s use Postman to test our endpoints. It’s a very useful tool to test RESTful APIs.

Open Postman and close the intro messages. You’ll see a screen like this one:

Change the GET selected by default into the select box to POST.

Type the API address into the Enter request URL field.

We have to provide the request body data to send to our API. Click on the Body menu item, then change the option displayed below it to raw.

Postman will show a Text option in the right. Change it to JSON (application/json) and paste the following JSON data below:

{

"name": ""

}

As you see, we’re going to send an empty name string to our new endpoint.

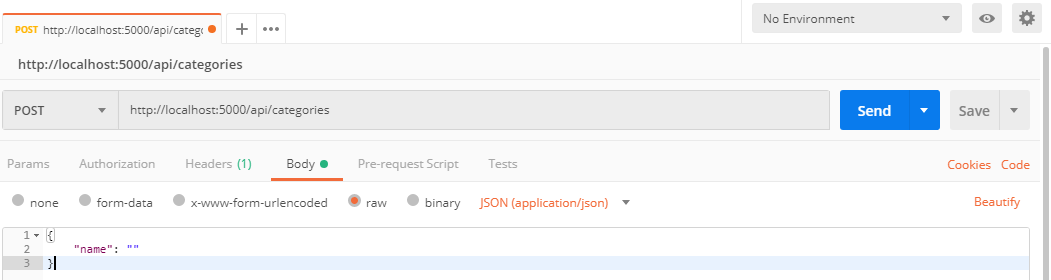

Click the Send button. You’ll receive an output like this:

Do you remember the validation logic we created for the endpoint? This output is the proof it works!

Notice also the 400 status code displayed at the right. The BadRequest result automatically adds this status code to the response.

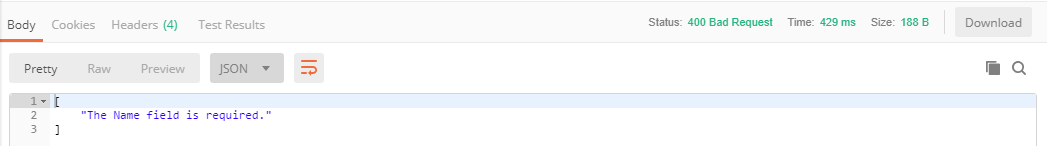

Now let’s change the JSON data to a valid one to see the new response:

The API correctly created our new resource.

Until now, our API can list and create categories. You learned a lot of things about the C# language, the ASP.NET Core framework and also common design approaches to structure your APIs.

Let’s continue our categories API creating the endpoint to update categories.

From now on, since I explained you most concepts, I’ll speed up the explanations and focus on new subjects to not waste your time. Let’s go!

Step 15 — Updating Categories

To update categories, we need an HTTP PUT endpoint.

The logic we have to code is very similar to the POST one:

- First, we have to validate the incoming request using the

ModelState; - If the request is valid, the API should map the incoming resource to a model class using AutoMapper;

- Then, we need to call our service, telling it to update the category, providing the respective category

Idand the updated data; - If there is no category with the given

Idin the database, we return a bad request. We could use aNotFoundresult instead, but it doesn’t really matter for this scope, since we provide an error message to the client applications; - If the saving logic is correctly executed, the service must return a response containing the updated category data. If not, it should give us an indication that the process failed, and a message indicating why;

- Finally, if there is an error, the API returns a bad request. If not, it maps the updated category model to a category resource and return a success response to the client application.

Let’s add the new PutAsync method into the controller class:

[HttpPut("{id}")]

public async Task<IActionResult> PutAsync(int id, [FromBody] SaveCategoryResource resource)

{

if (!ModelState.IsValid)

return BadRequest(ModelState.GetErrorMessages());

var category = _mapper.Map<SaveCategoryResource, Category>(resource);

var result = await _categoryService.UpdateAsync(id, category);

if (!result.Success)

return BadRequest(result.Message);

var categoryResource = _mapper.Map<Category, CategoryResource>(result.Category);

return Ok(categoryResource);

}

If you compare it with the POST logic, you’ll notice we have only one difference here: the HttPut attribute specifies a parameter that the given route should receive.

We’ll call this endpoint specifying the category Id as the last URL fragment, like /api/categories/1. The ASP.NET Core pipeline parse this fragment to the parameter of the same name.

Now we have to define the UpdateAsync method signature into the ICategoryService interface:

public interface ICategoryService

{

Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync();

Task<SaveCategoryResponse> SaveAsync(Category category);

Task<SaveCategoryResponse> UpdateAsync(int id, Category category);

}

Now let’s move to the real logic.

Step 16 — The Update Logic

To update our category, first, we need to return the current data from the database, if it exists. We also need to update it into our DBSet<>.

Let’s add two new method contracts to our ICategoryService interface:

public interface ICategoryRepository

{

Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync();

Task AddAsync(Category category);

Task<Category> FindByIdAsync(int id);

void Update(Category category);

}

We’ve defined the FindByIdAsync method, that will asynchronously return a category from the database, and the Update method. Pay attention that the Update method isn’t asynchronous since the EF Core API does not require an asynchronous method to update models.

Now let’s implement the real logic into the CategoryRepository class:

public async Task<Category> FindByIdAsync(int id)

{

return await _context.Categories.FindAsync(id);

}

public void Update(Category category)

{

_context.Categories.Update(category);

}

Finally we can code the service logic:

public async Task<SaveCategoryResponse> UpdateAsync(int id, Category category)

{

var existingCategory = await _categoryRepository.FindByIdAsync(id);

if (existingCategory == null)

return new SaveCategoryResponse("Category not found.");

existingCategory.Name = category.Name;

try

{

_categoryRepository.Update(existingCategory);

await _unitOfWork.CompleteAsync();

return new SaveCategoryResponse(existingCategory);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

// Do some logging stuff

return new SaveCategoryResponse($"An error occurred when updating the category: {ex.Message}");

}

}

The API tries to get the category from the database. If the result is null, we return a response telling that the category does not exist. If the category exists, we need to set its new name.

The API, then, tries to save changes, like when we create a new category. If the process completes, the service returns a success response. If not, the logging logic executes, and the endpoint receives a response containing an error message.

Now let’s test it. First, let’s add a new category to have a valid Id to use. We could use the identifiers of the categories we seed to our database, but I want to do it this way to show you that our API is going to update the correct resource.

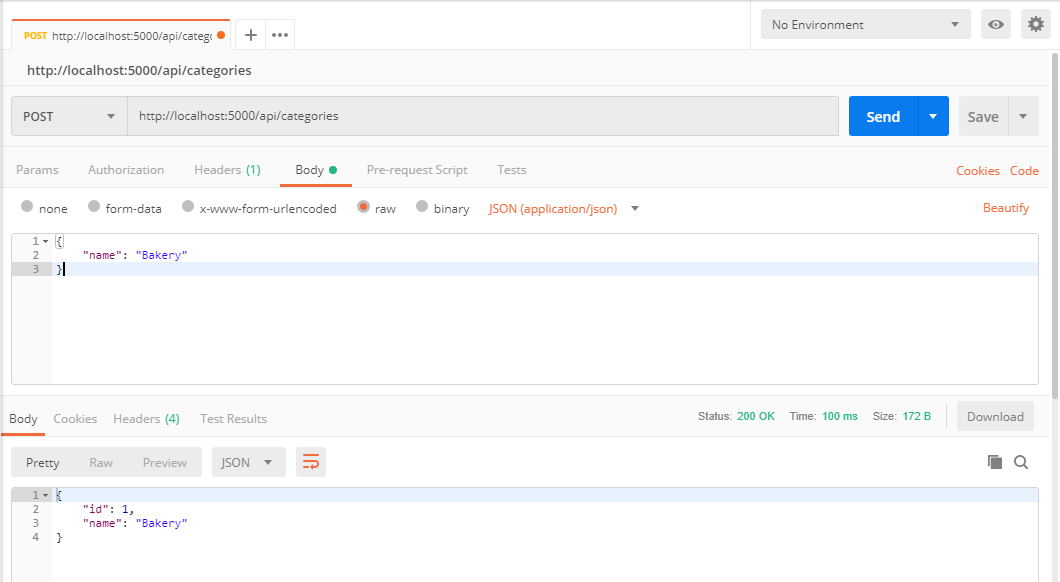

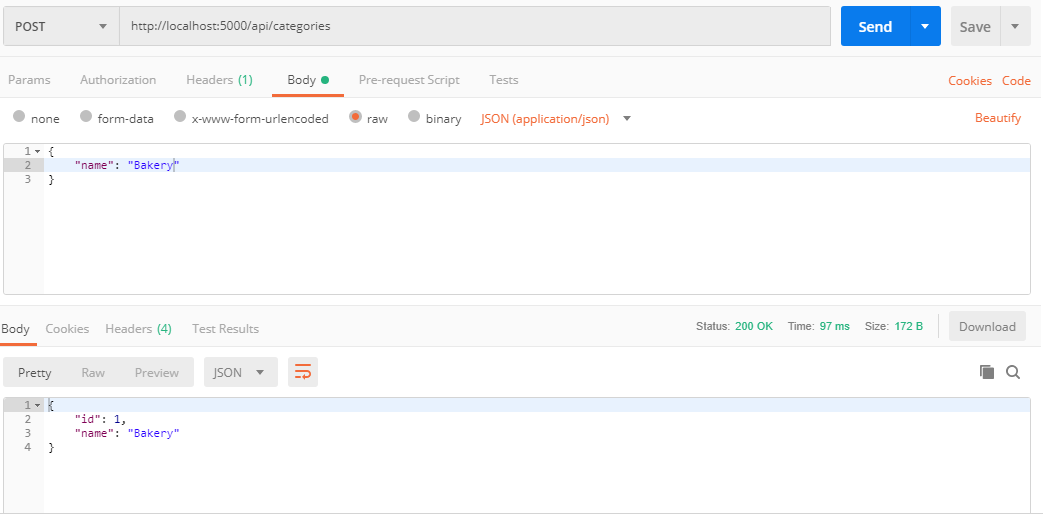

Run the application again and, using Postman, POST a new category to the database:

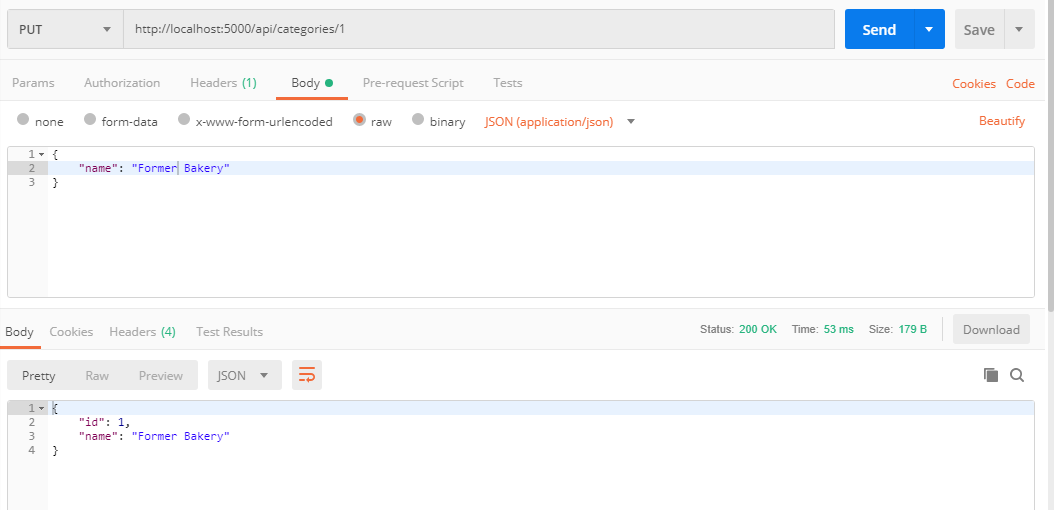

Having a valid Id in hands, change the POST option to PUT into the select box and add the ID value at the end of the URL. Change the name property to a different name and send the request to check the result:

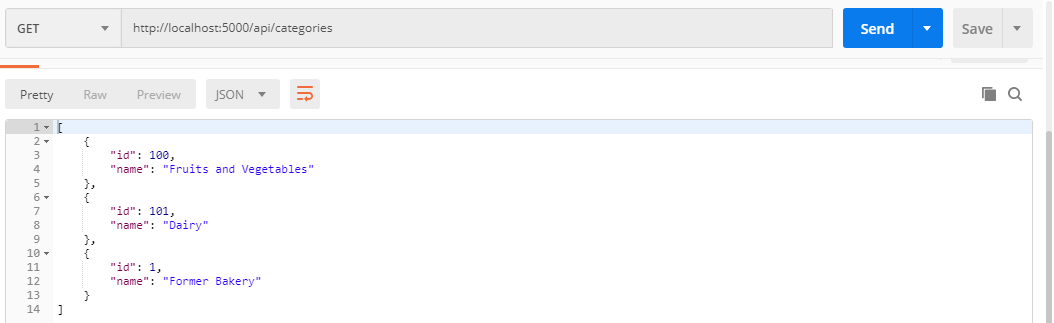

You can send a GET request to the API endpoint to assure you correctly edited the category name:

The last operation we have to implement for categories is the exclusion of categories. Let’s do it creating an HTTP Delete endpoint.

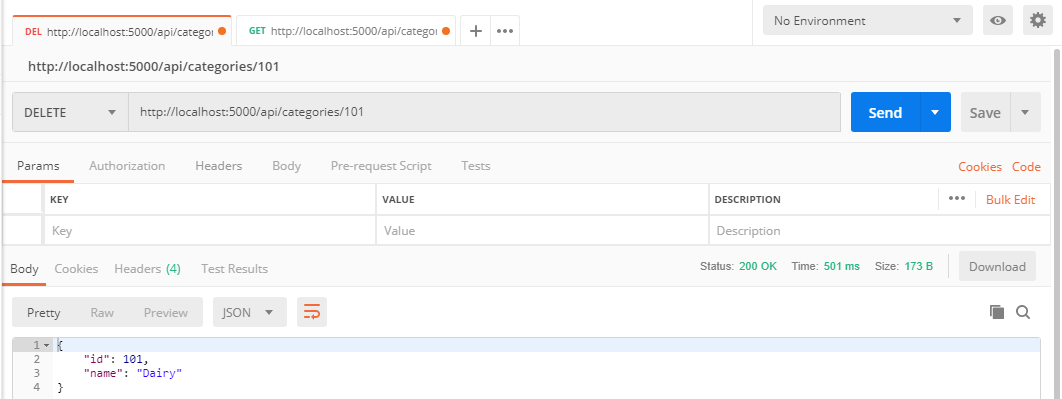

Step 17 — Deleting Categories

The logic for deleting categories is really easy to implement since most methods we need were built previously.

These are the necessary steps for our route to work:

- The API needs to call our service, telling it to delete our category, providing the respective

Id; - If there is no category with the given ID in the database, the service should return an message indicating it;

- If the deletion logic is executed with no problems, the service should return a response containing our deleted category data. If not, it should give us an indication that the process failed, and a potential error message;

- Finally, if there is an error, the API returns a bad request. If not, the API maps the updated category to a resource and returns a success response to the client.

Let’s get started by adding the new endpoint logic:

[HttpDelete("{id}")]

public async Task<IActionResult> DeleteAsync(int id)

{

var result = await _categoryService.DeleteAsync(id);

if (!result.Success)

return BadRequest(result.Message);

var categoryResource = _mapper.Map<Category, CategoryResource>(result.Category);

return Ok(categoryResource);

}

The HttpDelete attribute also defines an id template.

Before adding the DeleteAsync signature to our ICategoryService interface, we need to do a small refactoring.

The new service method must return a response containing the category data, the same way we did for the PostAsync and UpdateAsync methods. We could reuse the SaveCategoryResponse for this purpose, but we’re not saving data in this case.

To avoid creating a new class with the same shape to deliver this requirement, we can simply rename our SaveCategoryResponse to CategoryResponse.

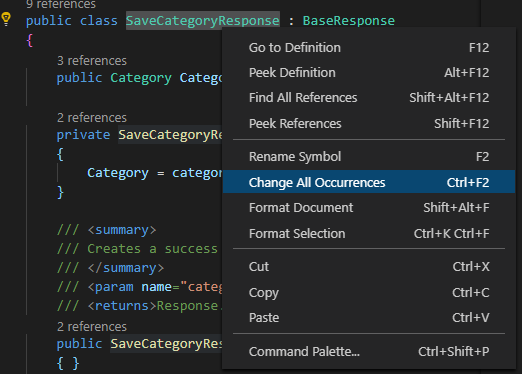

If you’re using Visual Studio Code, you can open the SaveCategoryResponseclass, put the mouse cursor above the class name and use the option Change All Occurrences to rename the class:

Be sure to rename the filename too.

Let’s add the DeleteAsync method signature to the ICategoryServiceinterface:

public interface ICategoryService

{

Task<IEnumerable<Category>> ListAsync();

Task<CategoryResponse> SaveAsync(Category category);

Task<CategoryResponse> UpdateAsync(int id, Category category);

Task<CategoryResponse> DeleteAsync(int id);

}

Before implementing the deletion logic, we need a new method in our repository.

Add the Remove method signature to the ICategoryRepository interface:

void Remove(Category category);

And now add the real implementation on the repository class:

public void Remove(Category category)

{

_context.Categories.Remove(category);

}

EF Core requires the instance of our model to be passed to the Removemethod to correctly understand which model we’re deleting, instead of simply passing an Id.

Finally, let’s implement the logic on CategoryService class:

public async Task<CategoryResponse> DeleteAsync(int id)

{

var existingCategory = await _categoryRepository.FindByIdAsync(id);

if (existingCategory == null)

return new CategoryResponse("Category not found.");

try

{

_categoryRepository.Remove(existingCategory);

await _unitOfWork.CompleteAsync();

return new CategoryResponse(existingCategory);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

// Do some logging stuff

return new CategoryResponse($"An error occurred when deleting the category: {ex.Message}");

}

}

There’s nothing new here. The service tries to find the category by ID and then it calls our repository to delete the category. Finally, the unit of work completes the transaction executing the real operation into the database.